Hello, readers! This month, I’m scrutinizing book sales in the first half of 2023, which entails crunching some numbers for Buffalo Street Books, comparing them to past years, holding them up to industry-wide figures, and then showing why that last activity is a ridiculous thing to do.

Sales are down. Perhaps you predicted the story would start that way? In-store book sales at Buffalo Street Books are down 12.7% from the first half of last year and online book sales are down a whopping 46.2%. Sales to schools and nonprofits are down 41.2%.

But wait!

Sideline sales are up by an astonishing 120% (sidelines are cards, notebooks, puzzles—anything not a book). Some of this increase appears to derive from a change in bookkeeping methods, in which a few items that used to be classified as books are now more properly counted as sidelines, but there’s definitely also a sales uptick there. And we’ve seen small but mighty increases in revenue from used books and events. This means that compared to the first two quarters of last year—plot twist—our total income is up by 2.16%.

That’s not enough to lift our income past previous highs. This year’s Q1 and Q2 are down 10.3% from 2021, the best year of the past five, and down 6.2% from 2019.

BSB’s fortunes track overall industry trends, only more so. According to Publishers Weekly, book sales for the first quarter were steady and then decreased slightly in the second quarter, for an overall six-month decrease of 2.7%. 2022 saw a 6.6% drop from 2021.

But here’s why comparing one bookstore to the entire industry doesn’t make sense. The reason national book sales didn’t decrease further in the first quarter of 2021 was because of one man: Prince Harry. Spare sold about 1.1 million books, enough to skew statistics all over the country—except in Ithaca.

BSB sold but 12 copies of the dear prince’s memoir, not nearly enough to make this story a fairy tale. (If BSB bought the $36 book from the publisher at a 45% discount, the store grossed $195; if it netted 2%, an aspirational goal, it is now richer by $8.64.) The same is true for the other giant new releases of the first half of 2023: Dav Pilkey’s latest Dog Man book, two Colleen Hoover titles, and Emily Henry’s romance novel, Happy Place.

(In fact, romance is this year’s fast-growing adult fiction genre—again, everywhere but at Buffalo Street Books. But not for lack of trying! Our general manager, Lisa Swayze, and several members of the staff (I’m looking at you, Nesiah and Isis!) are avid readers and ace recommenders of the genre. And did you know that one of our executive board members, John Jacobson, is an actual editor at Harlequin Books, specializing in authors of color, queer and trans authors, authors with disabilities, and authors of different religious and cultural backgrounds. John helps curate the BSB romance selection and they’ll be on a panel about queer romance this Saturday at the Ithaca is Books Festival—so if you are interested in reading more in this genre, BSB would love to seduce you.)

Lisa knew Prince Harry’s memoir wouldn’t sell robustly at BSB, because celebrity memoirs in general have never tempted our crowd, so she wasn’t stuck with stacks of unsold books. I mention this not only to flatter the refined and erudite tastes of those who shop at our store. In the first chapter of Open Book, I wrote about some of the paradoxes and counterintuitive truths of bookselling. Here’s a big one: everything that indie booksellers do best runs counter to the national trends in publishing. The Big Five publishers spend lavishly to create blockbusters which earn enough to keep their entire enterprises afloat. Booksellers, by contrast, know their own communities to a subtle degree and stay afloat precisely by ignoring marketing pressure from sales reps, sifting through the onslaught of books published each year, and selecting out the books that will be important and meaningful to their readers. Let’s underline that obvious, maddening, intractable point: publishers chase the books with the biggest payoff; indie booksellers chase the books with the best stories, the newest idea, the paradigm-shifting research, the voices we haven’t heard before. Lisa says that books about math do shocking well at BSB. This means that no indie bookstore is a microcosm of the larger bookselling landscape, a miniature version of the entire ecosystem. Indie bookselling is its own thing—tragically, triumphantly—and one of the many frustrations is how difficult it is to discern that in journalism and research and stats about the industry.

Questions I’d like answered about Spare and its ilk: did any indie bookstores make a significant profit from this book? If you follow the money, do most of the book’s profits flow to its corporate publisher (Penguin Random House) and corporate retailers (Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Target, Walmart, etc)? How often do indies help create blockbuster books; how often do blockbusters benefit indies? What should we change about this particular facet of the industry? If we could make a deal, would we enjoy a world where Amazon got to sell Spare if that meant it would keep its hands off, well, virtually every other book?

The Next Chapter of Open Book

Buffalo Street Books is taking big strides into the future by opening a reading room adjacent to the store, a community space for more events and also more hanging out. Next month, I’ll talk about what is entailed in the seemingly simple process of opening an empty room and think hard about bookstores as a “third place” (if home is the first place and work is the second place) in an era of diminishing communal areas.

Book Recommendations

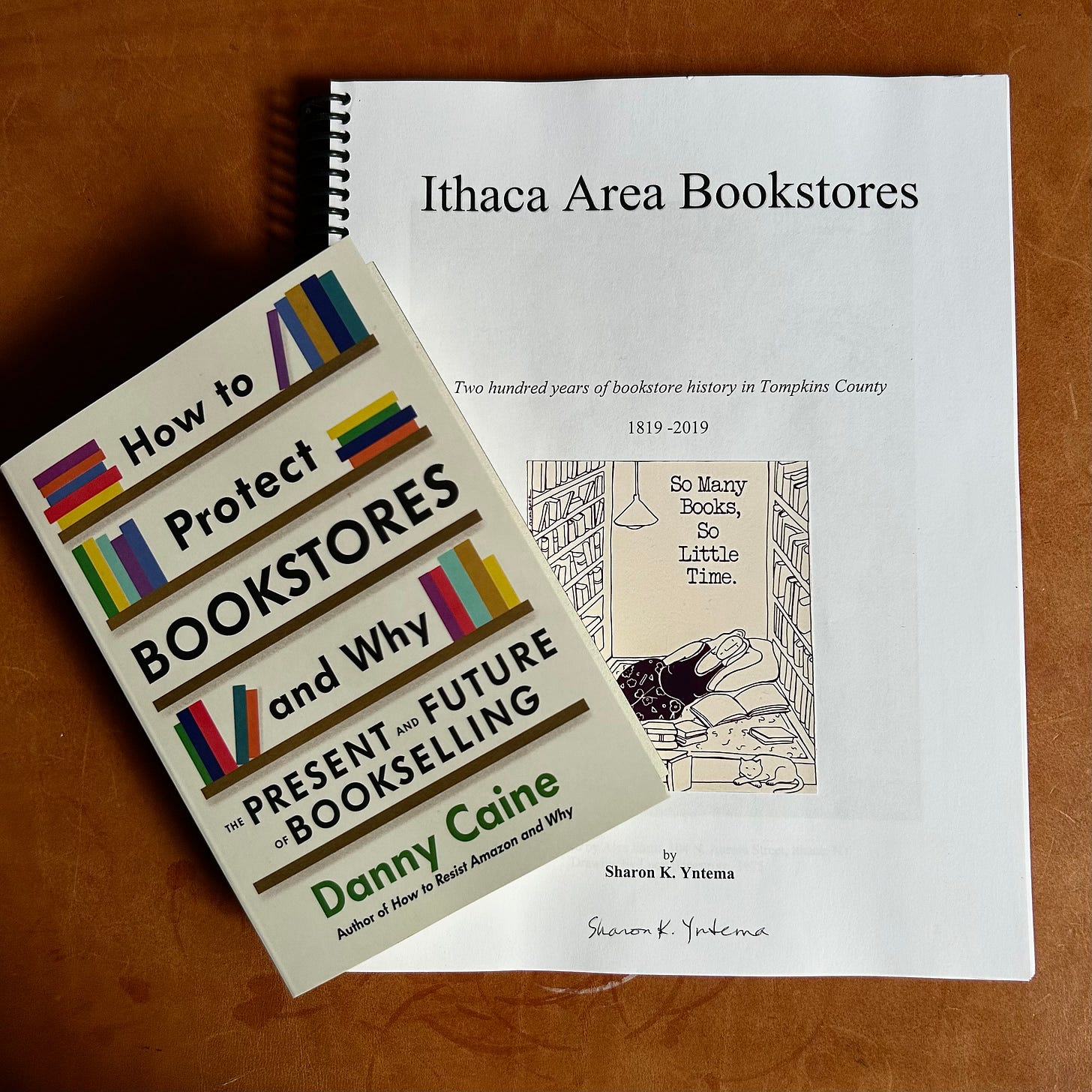

Ithacans, take note! Sharon Yntema has written and self-published a marvelous book, Ithaca Area Bookstores, that covers 200 hundred years of bookstore history in our town, literally dozens and dozens of stores. I know Sharon from when she was on the Executive Board at BSB, and before that she was the bookkeeper. She tells spicy tales from her tenure at Buffalo Street Books, and plenty of stories from gone-but-not forgotten stores. She also includes other voices, like a patron’s fond remembrance of the feminist Smedley’s Bookstore and another patron’s essay on how a bookstore should smell. Please check out Sharon’s book at BSB, on the website, and at the Book Fair at the Tompkins County Public Library, part of this weekend’s Ithaca is Books Festival.

Danny Caine, who you might know as the author of How to Resist Amazon and Why, has just released a new and longer book, How to Protect Bookstores and Why. This is an expansion of his zine, 50 Ways to Protect Bookstores. He profiles twelve innovative bookstores around the country and goes deep into their origin stories and their pivotal moments. From each story, he extracts a slew of incredibly thoughtful and hard-hitting recommendations for actions that individuals can take, as well as larger structural change that will support a healthy literary ecosystem. This book affirmed so much of what I have come to believe, and it also made me think hard. At the beginning of the book, Caine explains why he doesn’t use the words “indie” or “independent” in the title. And at the end of the book, he has this to say:

“What if bookstores aimed for collectivity rather than independence? That could look like collective ownership and the rise of a business model that no longer relies on the use and regeneration of a single person’s wealth. It could mean increased collectivity among bookstores—the threats outlined in this book are certainly big enough to warrant more collective action. Of course, it could also mean collective action by booksellers to improve the dignity of their work.”

Yes, that. All of it. And here’s another parting thought. After going into great detail about the astounding work that booksellers to do keep the lights on, he asks:

“[W]hat could be done if bookstores didn’t face such steep odds just to stay open, let alone do the innovative and inspiring community work discussed in this book. What if the world functioned in such a way that made it easier, not harder, for bookstores to do what they do so well?”

I love this one!