Chapter 5: Open Letter to MacKenzie Scott, Novelist

...for you to forward around the webs in the hope of reaching her

Dear Ms. Scott,

I write to you as one reader and writer to another. You are leading an extraordinary life, and I respect how much of it you’ve conducted in dignified silence. I don’t know you, yet I think there are a few broad assumptions that I can make from what we share—a love of reading and a training in writing—as well as from your novels themselves.

My first question, my first burning curiosity: what is your pseudonym? Or should that be plural—your pseudonyms? Go ahead, you can whisper it in my ear; I won’t tell. I would never want to spoil your fun. You’ll just never get me to believe that after studying creative writing with Toni Morrison at Princeton and publishing two critically acclaimed novels, you simply stopped writing. No writer does it for the money, so a sudden influx of cash—okay, the steady growth of a world-conquering fortune—isn’t likely to touch the root of your ambition to shape stories. Sure, you were a little busy in those early years, helping to build Amazon and raising four kids while writing your first book. And yes, that unignorable surname on a novel being sold on Amazon hampered rather than helped sales, making it complex for readers to judge the worth of your words. So I know you just changed the name and kept on writing. Maybe you have been writing without publishing? But somehow I doubt it.

Second question: what do bookstores need for authors like you, from philanthropists like you? How are these two parts of your extraordinary life talking to one another? Is there anyone on the planet better positioned than you to think through the quandary that is independent bookselling, as someone who has arguably won ($35 billion) and lost (a writing career, a husband) the most from the metasizing of Amazon?

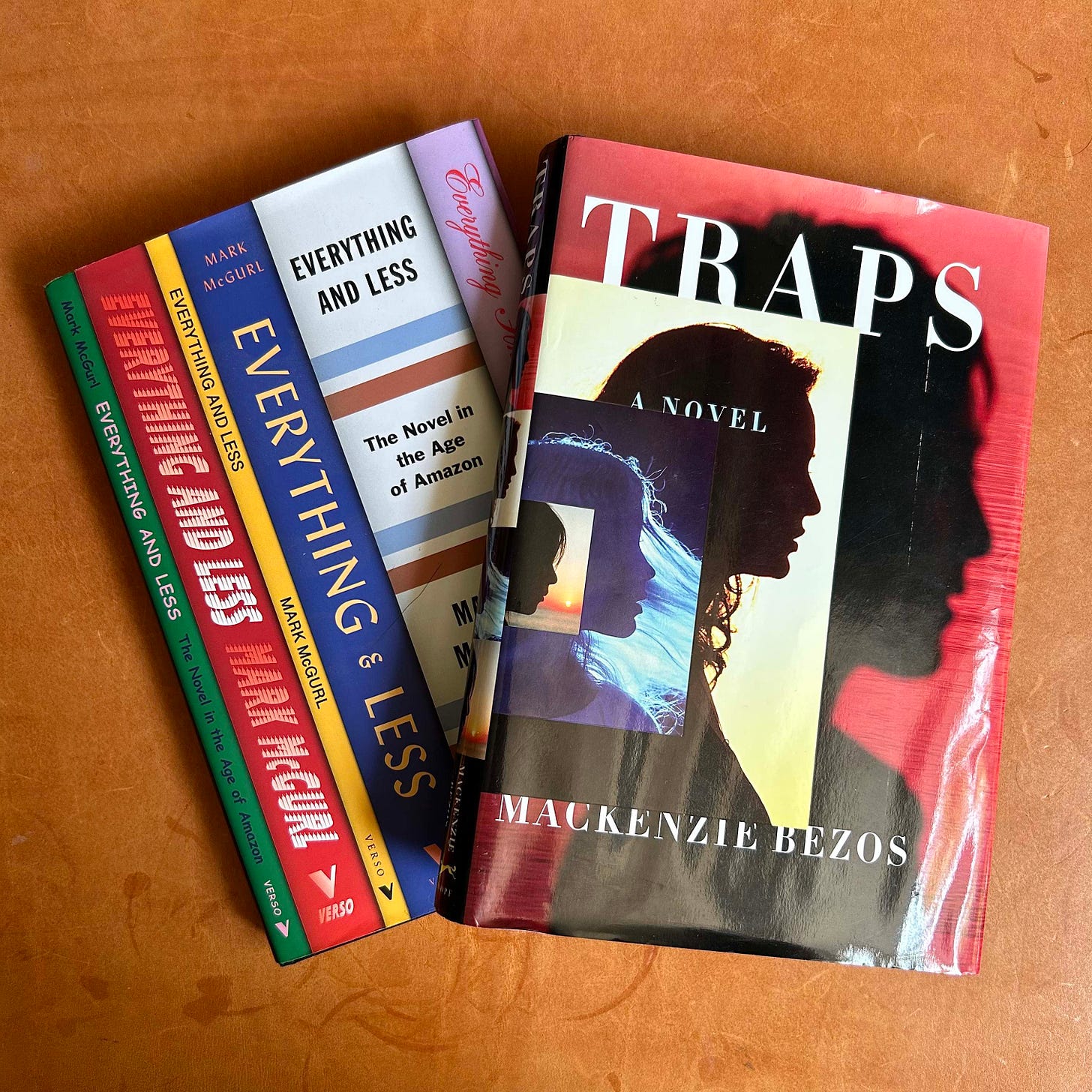

Is there anyone on the planet better positioned than you to counteract Amazon, you who took ten years to write your first novel—The Testing of Luther Albright (Harper, 2006)—ten years in which you were simultaneously working against your own best interests by helping to build a corporation that would slay independent bookstores? You who published your second novel—Traps (Knopf) in 2013, the absolute nadir for indie bookstores, the year of lowest sales, the year in which it was hardest of all for a midlist literary author like yourself to break through, all because of your husband’s sinister devaluing of the book?

The problem, stated in the baldest possible terms, is that it is not currently possible to make a profit or even break even by selling new books as an independent bookseller. How can this be? Shouldn’t it be dead simple? Books are an addictive pleasure and book sales are on the rise. The answer, stated in the baldest possible terms, is that readers can buy a book on Amazon for cheaper than booksellers can purchase it from the publisher to resell. And booksellers labor under other structural constraints unique to the industry; they must try to eke out a profit between the fixed list price set by publishers and the low discounts that publishers offer stores. That tiny amount is gobbled up by rent and payroll. According to the American Booksellers Association, the average profit margin is 1.5%, but it’s far less for stores that pay their booksellers a living wage. It’s a perversion of capitalism in which selling more books won’t help indie bookstores. It will always cost more to sell your book than indie bookstores will ever get back. Out here in the real world, you can’t profit from a negative number.

Here's the thing: I firmly believe that indie bookstores do not need saving. I own a bookstore—well, a share in a community-owned bookstore—and for the past five years, I’ve served on its executive board, so I’ve ridden the rollercoaster of our balance sheets, all those white-knuckled plunges followed by heroic, fleeting rescues. I can testify that it is exhausting and dysfunctional to continually ask our patrons to bail us out of financial difficulties, and even if you, as the country’s most generous philanthropist, were to replicate that on a larger scale, it wouldn’t touch the root of the problem. Truly, we don’t need you to swoop in and bestow pots of free money as you have for so many nonprofits and universities, even if that idea sparkles like seduction, like salvation.

Instead, indie bookselling needs to be restructured. Booksellers, readers, and writers need the industry to be reorganized for sustainability, so that all our needs meet, interlock, and mutually reinforce one another. Our interests are naturally aligned yet currently torqued by a demonic monopoly. So my big question to you, to the novelist who knows what it means to be at war with yourself, to have your own interests subverted and placed in opposition, is this: what would it look like if indie bookselling were designed according to the needs of readers and writers?

And how do we get there? We almost certainly get there with a massive infusion of capital from outside the literary ecosystem, not as a bandaid but as an historic paradigm shift, a dramatic revisioning of the possibilities, as when Andrew Carnegie funded public libraries, or right now when nonprofit news organizations are reinventing journalism. You must have thought about this. I sure have, and here are three ideas.

Maybe this means a fund to endow bookseller positions at cooperative, nonprofit, and mission-based bookstores to help widen the profit margin and secure well-paid, low-turnover jobs that often act as gateways into literary careers. Maybe this means creating a legal fund for bookstores that are interested in converting to a cooperative or nonprofit model. Maybe this means investing in entrepreneurs interested in opening community-owned bookstores in book deserts to serve poor or underrepresented readers, a problem which has mostly been discussed in terms of children’s literacy but which equally affects the adults in their lives.

Here's what I know about you from reading your second novel, Traps, which—I must confess—I did not expect to be so distinctive, so beautifully a departure from the bland, third-person narration of so many realist novels by and about women, so innovative in its use of narrative perspective. I know that you are an exquisite, almost painful noticer as you peer remorselessly at the gestures and actions that reveal the interiors of your characters. I know that you think in precisely the terms I have used in this letter, as you portray the interlocking, mutually reinforcing needs of four women whose lives converge over the course of four suspenseful days. I know that you care about how artists transmute the anguish of their lives into their work, as you write with astonishing dimensionality about a famous actress with a fierce desire for privacy. I wonder how those values have informed your work since taking control of your fortune. I wonder what you are writing, and I’m in suspense about what you do next.

Yours,

Amy Reading (not a pseudonym)

The Next Chapter of Open Book

In August, I’ll look back to the first half of 2023 and provide some financials for Q1 and Q2 at Buffalo Street Books, as well as the industry at large.

Book Recommendations

Support indie bookstores on Amazon’s Prime Day! Bookshop.org has free shipping on July 11th and 12th. And you never pay shipping when you go to your local indie and pull a book right off the shelf and begin reading it immediately.

Everything and Less: The Novel in the Age of Amazon by Mark McGurl looks at how Amazon’s monopoly has affected the writing that is sold on its platform. McGurl’s argument, here and in the hugely influential The Program Era: Postwar Fiction and the Rise of Creative Writing, is that the structures and institutions in which writers work leave traces or “watermarks” on the literature they produce. The Program Era argues that the university and the rise of MFA programs was the most significant development in 20th century literature; Everything and Less posits that Amazon and “platform capitalism” have driven popular and literary fiction in the 21st. He looks at MacKenzie Scott’s novels, as well as the “self-pitying billionaire” of E.L. James, the self-published titles scrolling from Amazon’s Kindle Direct Publishing, and the mapping of the world—and the world wide web—in genre fiction and literary fiction (this book is out of print but available used from Bookshop; the paperback will be published in January).

I was absolutely riveted and enthralled (yes, riveted and enthralled) by Anne Berest’s The Postcard, a much-typed book that totally lived up. I love a good quest in which the narrator has a burning question and the book is the story of her making steady, suspenseful progress toward the answer (call it the glorification of scholarship for the research nerds among us). The Postcard begins when the narrator’s mother receives an unsigned postcard with the names of her parents, aunt, and uncle, all of whom were killed at Auschwitz. The narrator begins to uncover the unspoken stories of her family’s Jewish heritage and the reasons behind the silence. Heartbreaking and full of heart and written with propulsion.