Chapter 10: Feminism is Like Indie Bookselling

…on collectives and collections and radical lesbians

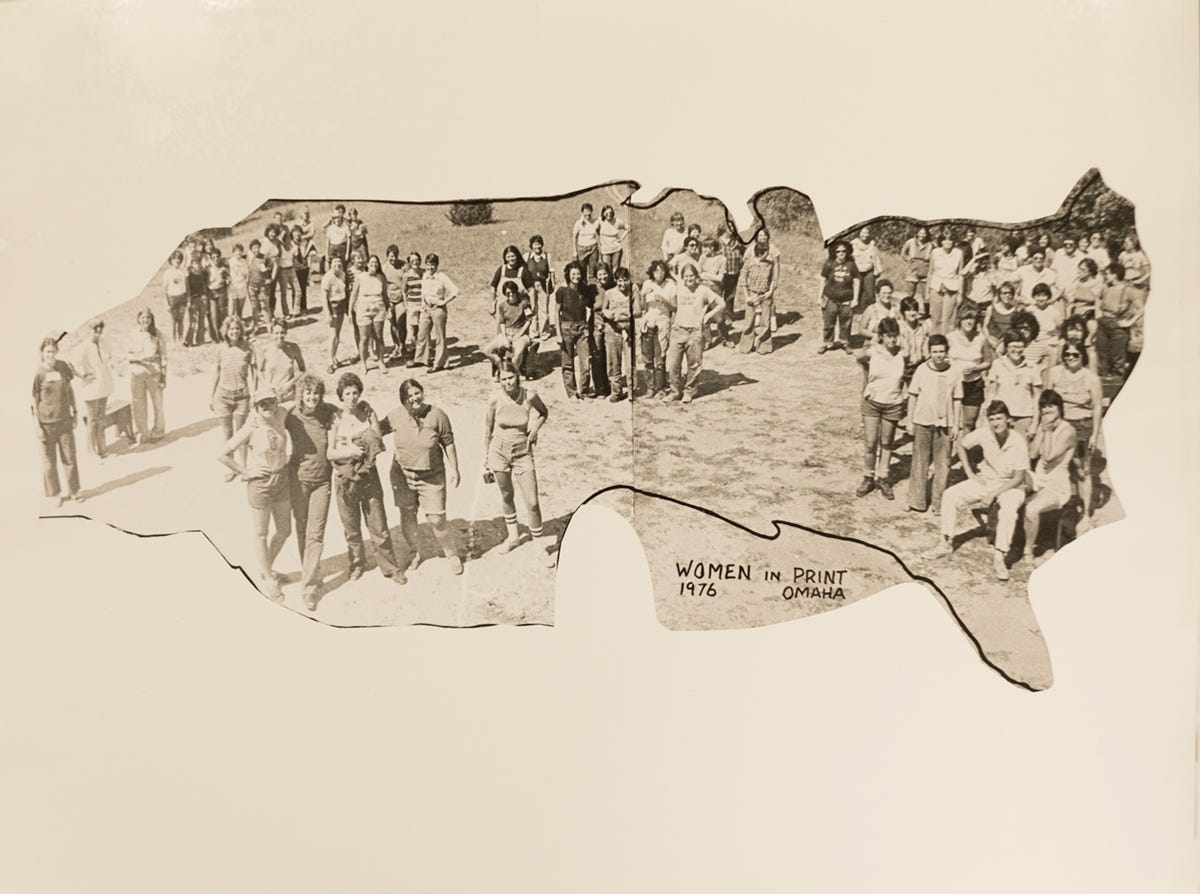

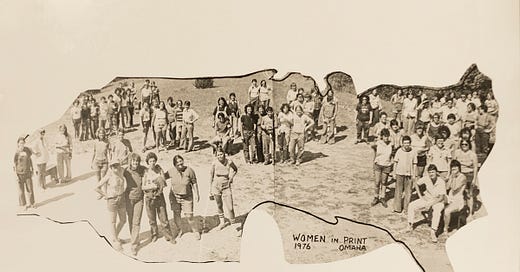

On a hot August week in 1976, one hundred and thirty two feminist booksellers, publishers, and printers converged in Omaha, Nebraska for the most pivotal event in American literary history you’ve never heard of.

The novelist and publisher June Arnold convened the first Women in Print conference—and she chose a Campfire Girl campground in the middle of nowhere because it was geographically equitable. She designed a formal program of workshops, and she set a bunch of rules: each feminist organization could send two representatives; no organizations that included men could be included unless they were “Third World feminists working on Third World projects” with men; the conference would be kept secret; no writers would be invited, only workers in print media.

That week, the women shared skills in morning workshops and talked theory and politics in afternoon sessions. Then they took off their clothes and went swimming. One day, they sketched a map of the United States in the gravel and everyone stood on their state for a photograph—their power and reach made visible.

By the end of the week, they’d codified a radical feminist separatist vision of print culture, autonomous and women-centric. They would share information through a communications network; use their bookstores broadly as shelters and information centers for women; continue to develop their politics; learn how to manage the contradictions between radical politics and capitalist business practices; hold themselves accountable to one another; support all feminist media; and create a feminist “books in print.”

My argument: when it comes to contemporary best practices for indie bookstore survival in late-stage monopoly capitalism, lesbian feminist separatist booksellers did it first and did it better.

The Rise of Feminist Bookstores

The first two bookstores to self-identify as feminist were ICI: A Woman’s Place in Oakland and Amazon in Minneapolis, both of which began in 1970. ICI grew from the Bay Area Gay Women’s Liberation into a large collective that was diverse in race, class, and sexuality. As historian Kristen Hogan observes, in contrast to other Second Wave organizations, feminist bookstores were “already lesbian and multiracial” from their beginnings. As women traveled to these bookstores, they brought ideas back home with them, and some of them founded their own bookstores. The numbers tell the story:

1976: 14

1977: 86

1978: 96

At the height of the movement, there were 130 feminist bookstores allied with each other across the globe.

Smedley’s Bookshop in Ithaca was absolutely typical of this fervent time. As I learned from Sharon Yntema’s book, Ithaca Area Bookstores, in 1976, three women—Camille Tischler, Harriet Bronsnick, and Kate Dunn—raised $10,000 in loans from friends to open a radical feminist bookstore at 119 E. Buffalo Street (what is now a real estate office in the brick rowhouses next to Buffalo Street Books). EDITED: Harriet soon reverted to her maiden name, Alpert. They organized themselves as a non-hierarchical collective, and they packed their small shop with around 20,000 books and periodicals from small presses—titles that you could find nowhere else in upstate New York. Later they expanded to include gallery space and meeting space for political study and consciousness-raising groups. They paid back their loans but earned no profit; they considered themselves an information center for women and men, activists and academics and lifelong learners. They later sold the bookstore to Zee Zahava, and you can read a lovely ode from a queer academic who relied on its offerings here.

Feminist Bookstore News

During that summer week in Omaha, Carol Seajay, one of the founders of ICI, got inspired enough to come home and start Old Wives’ Tales in San Francisco, and she also made plans for a newsletter that would link feminist booksellers across the nation (and eventually beyond). Three bookstores contributed the funds, and Seajay began with just a few folded legal-size pages per issue, mailed to subscribing “bookwomen,” whom she defined as women working in women-only bookstores. At the heart of the newsletter were lists: of books by Spanish-language, Native, and Black female authors, of new feminist bookstores, of small presses, of the three feminist book distributors that were in business by 1976. The issues grew longer, bristling with letters to the editor, announcements, political discussions, skill-sharing tips on how to resist the Literary Industrial Corporate Establishment (LICE), and columns of every sort.

By issue three, controversy raged: should women publishers be allowed to subscribe? Was the information they were sharing valuable enough to keep to themselves and confer a competitive advantage? Was it important to keep independent even from feminist publishers in case they needed to take action against them? Seajay compromised—she allowed publishers to subscribe and started a second, booksellers-only digest called Hot Flashes.

The FBN did not just report on the state of feminist publishing and bookselling—it sought to influence it. Seajay and other contributors could drum up advance orders for important titles to ensure that the publishers would then increase marketing and publicity budgets for them. They worked tirelessly to get forgotten titles back into print, including Joanna Russ’s sci-fi classic, The Female Man and May Sarton’s As We Are Now. Kristen Horgan writes, “women’s writing went mainstream in part because feminist bookwomen proved (and proved again) to an interminably skeptical mainstream press that readers were looking for it.” They got creative with the detritus of a ruthless industry; for instance, one bookstore would buy all the remaindered copies of an underpromoted title and become the distributor for it, which they’d announce in the FBN. They sold so many copies of out-of-print books by Adrienne Rich and Mary Daly that they voluntarily sent the authors a portion of their proceeds. But many feminist booksellers, including June Arnold, believed that women who published with traditional publishers were betrayers who sold out to a patriarchal system that only wanted to profit from the fad of feminism. The driving goal for most feminist bookwomen was to own and control the means of production.

In 1984, when my friend, fellow Ithacan, and high-caliber badass Nancy Bereano started her lesbian press, Firebrand Books, she announced it in a letter to the Feminist Bookstore News.

I’d argue that the secret underlying the history of the Feminist Bookstore News is that many of the bookstores in question were collectives which served their members as much or more than their customers: workers radicalized each other, taught each other how to build bookshelves and balance spreadsheets, held each other accountable to antiracist ideals, and obviously slept and broke up with each other. And much of the work that the FBN did involved collection. The booksellers collected like-minded books, so if one title particularly struck you, there’d be a dozen more alongside it on the list or shelf to pull you along. And they collected like-minded bookstores so that women could find them. When Womanbooks opened in Manhattan, someone came from Australia on their second day and bought hundreds of dollars’ worth of books—solely because Womanbooks appeared in a guidebook for feminist readers. The power of grouping like with like is the power of discovery and the momentum of building on something that is working.

The Fall of Feminist Bookstores

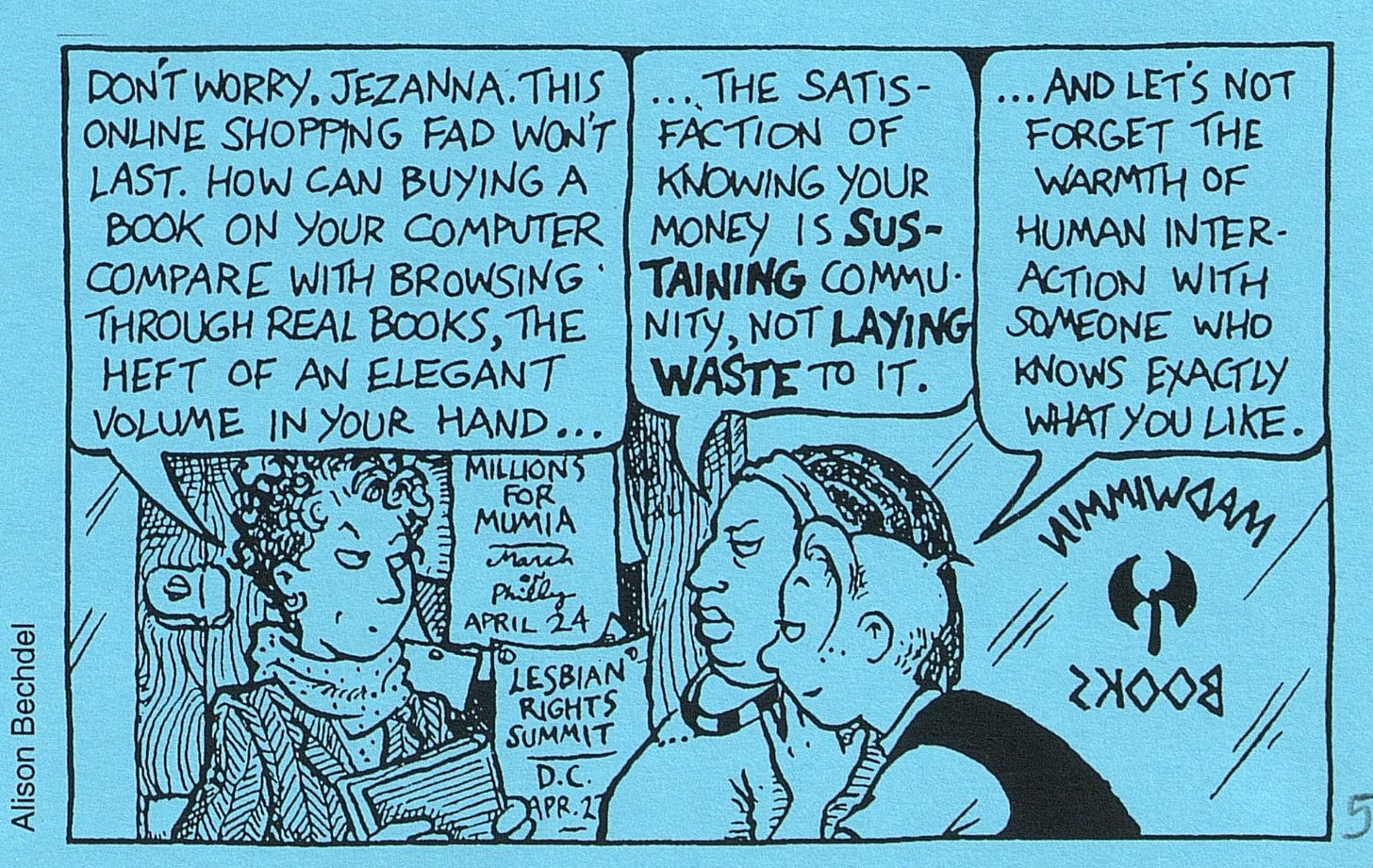

The FBN served as the vanishing mediator between separatist feminists and today’s indie agitation against Amazon. In 1992, Seajay herded her subscribers into a new organization, the Feminist Bookstore Network, whose purpose was to act as a lobbying group within the ABA. But soon the network became the lobbying arm for all independents to resist the crushing effects of multinational publishing and chain superstores. The network spearheaded a lawsuit for anticompetitive practices that netted indie bookstores a $25 million settlement in 1997.

The tactics and theory of resistance to patriarchy translated well to resistance to corporate hegemony, but they were not successful. Feminist bookstores by the numbers:

1998: 175

2003: 45

As the numbers plummeted, Seajay’s subscriber base vanished, and she ceased publishing the FBN in 2000 after twenty-four years of five to six issues per year. (In 2004, she started Books to Watch Out For, a digital newsletter for the feminist and LGBTQ literary markets and it ran at least through 2014. If anyone knows more about Carol Seajay’s story in the 2010s, let me know).

Today, only five of the original feminist bookstores from the 1970s remain open: Charis (Atlanta), A Room of One’s Own (Madison), BookWoman (Austin), Women and Children First (Chicago) and Antigone Books (Tuscon). EDITED: make that six bookstores: Womencrafts in Provincetown, MA has been operating since 1976. Thank you to Susan Eschbach for the corrections.

Charis Books maintains a list of feminist bookstores which currently numbers 25, including three in New York state.

Book Recommendations

The story told here comes from The Feminist Bookstore Movement: Lesbian Antiracism and Feminist Accountability by Kristen Hogan, a Duke University Press book that arose from Hogan’s dissertation at the University of Texas. A much shorter summary of this history can be found in Trysh Travis’s scholarly article, “The Women in Print Movement: History and Implications.”

For something completely different, may I tempt you with My Death by Lisa Tuttle. This short, taut novel captivated me completely. It tells the story of a writer at loose ends who hits upon the idea of a writing a biography of the woman who modeled for her favorite painting; when she arrives to interview her, she finds that the woman is expecting her and she is drawn down an inescapable path. It strongly reminded me of The Thirteenth Tale by Diane Setterfield, an extremely satisfying audiobook (which, strangely, also comes in an abridged version should you need a quicker gulp).

Happy reading and listening!

This was awesome. Thank you for it!!